End Cyber Abuse is a global collective of lawyers and human rights activists working to tackle technology-facilitated gender-based violence by

- raising awareness of rights

- advocating for survivor-centered systems of justice, and

- advancing equitable design of technology to prevent gendered harms.

We seek to learn from and disseminate best practices across jurisdictions to better equip those on the ground facing such cases. On March 17th, 2021, End Cyber Abuse hosted a workshop at MozFest, ‘Mini-Hackathon on Tackling Technology-Facilitated Gender Violence (TGBV).’ We aimed to ideate around the possible technological solutions that would help guide survivors of TGBV in understanding their rights and options, as well as seeking support.

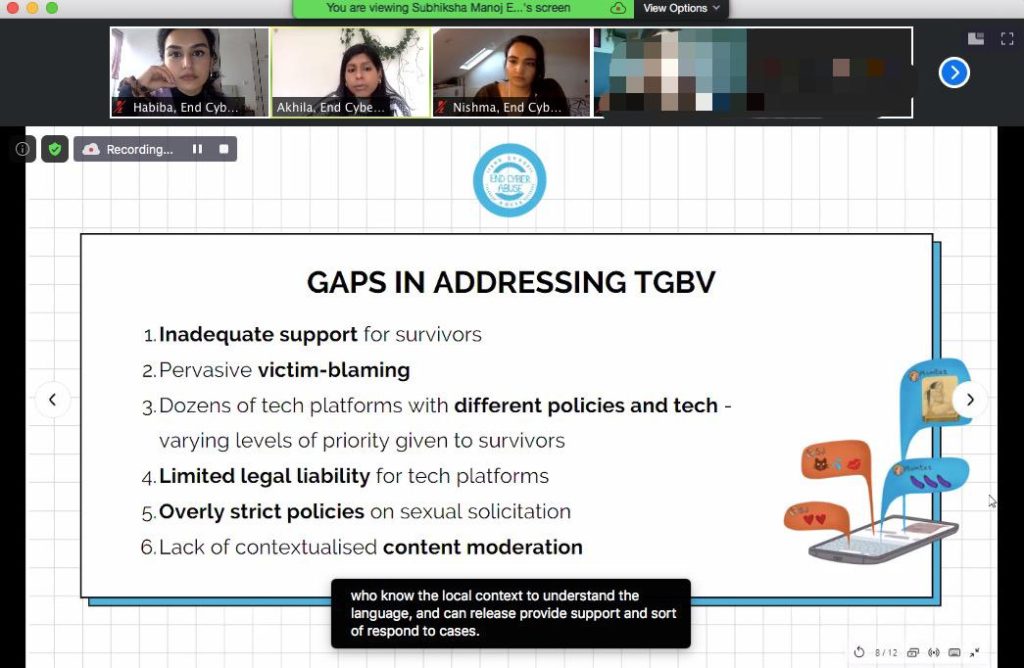

Gaps in addressing TGBV

Technology-facilitated gender violence is a broad spectrum of online behaviours perpetrated by one or more people where digital tools and technology are used to harass, intimidate, surveil, and inflict violence upon victims. Such behaviours can have both online and offline consequences for victims.

Examples of TGBV include:

- Image-based sexual abuse – taking or sharing someone’s intimate images without their consent. Images might be shared with friends, family members, employers, posted on social media, or posted on porn tube sites.

- Forcing your partner to share passwords or intimate images – often takes place in the context of an abusive relationship

- Cyberstalking – installing spyware or stalkerware to follow someone location, or monitor their conversations or other online activity

- Doxxing – revealing personal or identifying documents or details online (e.g. home address, government ID, phone number) about someone without their consent

- Online harassment – repeatedly targeting an individual or group through tactics like hate speech that targets someone’s identity, like gender, sexual orientation, race or religion — or threats of physical or sexual violence or assault, or more.

- Deepfakes – using deep-fake technology, a form of artificial intelligence, or photoshop or other software, to alter an image, for instance by stitching an image of someone’s face onto an image of someone else’s nude body.

There are many gaps in the approaches we currently have to addressing TGBV. The slide below outlines a few that we discussed at the beginning of the workshop.

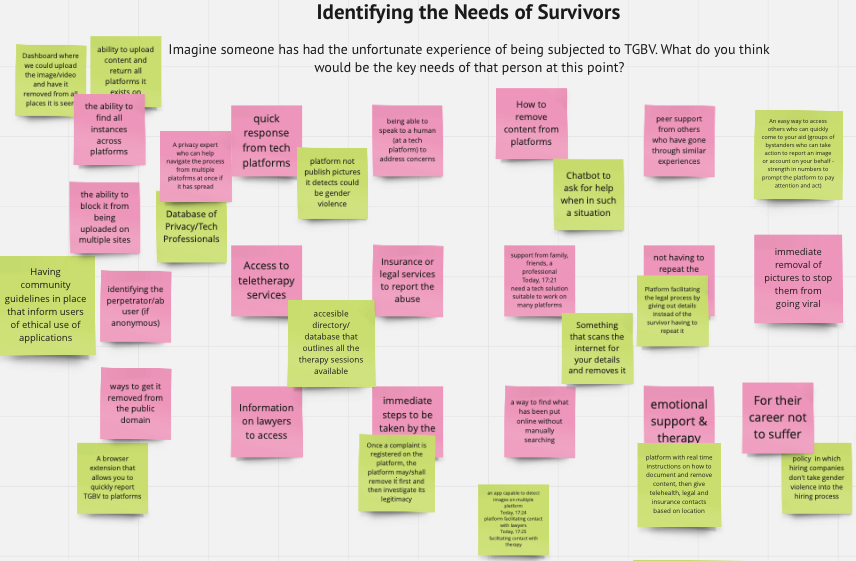

Identifying the needs of survivors

Participants were asked to imagine someone who has had an unfortunate incident of being the target of TGBV, and asked to identify what they envision to be the key needs of the survivor. The most popular answer was the removal of intimate or sexual images that have been shared online without consent — addressing a common form of TGBV, known as image-based sexual abuse (IBSA). In these cases, time is of the essence when it comes to image removal, and this can be a tricky terrain to navigate due to the number of obstacles in place for survivors, such as the delayed reaction time of platforms, the material being quickly and easily re-uploaded on multiple platforms, and the inability to often access a human moderator. When an image goes ‘viral’ online, it can be incredibly retraumatizing for the survivor, and almost impossible to monitor and request removal expediently.

Other needs that arose included freely accessible legal services which could help survivors in the image removal process and begin taking legal action against individuals and tech companies. This coupled with emotional support services proved to be the most urgent in identifying the needs of survivors.

Ideating tech-based solutions

Participants were then asked to identify potential solutions to the needs of survivors that they had identified. Together, they ideated ways of countering digital harm, as categorised below:

1. Tech Platforms

Many participants focused on the role of tech platforms in combating TGBV and image-based sexual abuse in particular, through secured and centralised systems of data sharing. One idea that generated interest to more effectively remove harmful or non-consensual images from the web was a model of inter-platform collaboration that allows platforms to view each other’s databases, filter through offensive material, and assign it a digital fingerprint, therefore allowing it to be swiftly identified and removed across platforms. This could help ensure it is no longer re-uploaded. This, of course, sounds utopian in its vision — as it was felt that it was unlikely that Silicon Valley tech platforms would hand over valuable user data to their competitors, without incentives aligned in that direction. Other ideas included improving on existing image scanning mechanisms and having better software in place to detect image-based abuse and private videos.

2. New software

Attendees also suggested new software built to detect and remove multiple instances of images and videos at once in the form of a browser add-on extension. Similar to the idea above, the detected images would have a unique code (digital finger-printing/hashing) so it can be easily identified and removed across platforms and websites.

3. Other

Other ideas included copyrighting images, similar to the way music is copyrighted, so an external regulatory body would be able to flag the material.

The idea that really resonated with participants was to design an effective model that can preemptively block images from being re-uploaded on platforms.

Designing solutions

After ideating tech-based solutions, participants were split into breakout rooms to bring their idea to life. One group suggested a novel way of creating a consortium of resources between platforms, including a shared database with hash technology that could block the content on all sites once reported on a single one. For example, Facebook’s internal policy with Revenge Porn Helpline UK. Users report the abuse to a single site which is then fingerprinted. This unique fingerprint is then shared with other UGC sites where it is blocked. This prevents it from being re-uploaded. Users get a notification if opted in about the final outcome.

Another solution included using age verification methods (this could include a driving license, a passport, or other legal documentation) on platforms before a user is allowed to publish content or interact with others. This is already in use by Pornhub. This would then be stored in an internal database and be flagged if the user posts inappropriate content.

To conclude, participants to our event provided detailed and creative insight on using pre-existing tech in novel ways to tackle technology-facilitated gender violence, centred on the needs of the survivor. You can watch a recording of our Mozfest event here.